Biodiversity, Extinction, Toxins and the Anthropocene

Humpback whales were almost extinct until by international agreement and law we stopped hunting them. Whales are critical to the ocean ecosystem and they even lock up carbon! We still threaten cetaceans with noise and plastic pollution, fishing lines and nets, and injuries from ocean-going vessels.

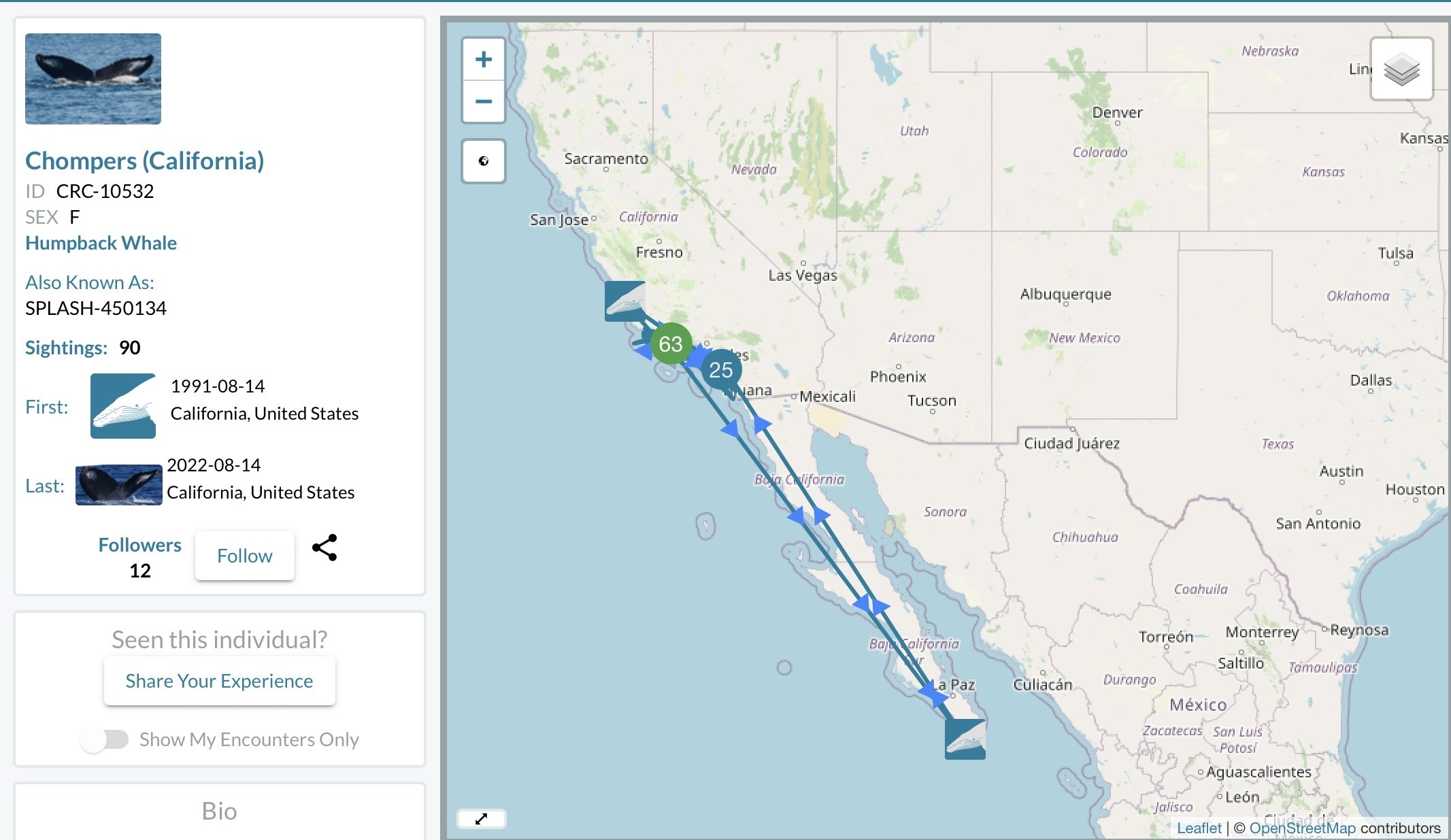

We spotted this humpback whale named “Chompers” (or SPLASH-450134) off the coast of California near Santa Barbara in 2011 and submitted a picture of its fluke (that is how they are identified, the patterns of white are very unique to an individual), to the Happy Whale website. We now get regular updates. You too can be a citizen scientist!

Many of the problems we experience in the environment are in large part due to efforts to feed and supply the energy needs of a rapidly growing population, teamed up with the race for short-term profits (as opposed to modest profits and long-term investments and values such as sustainability). So, we burn vast amounts of fossil fuel, cut down forests, dam rivers, create huge amounts of waste, and poison our own food and the environment.

We have been very successful using technology and science to feed the world, increase affluence in many low to middle income nations and so decrease poverty, prolong lifespans and decrease infant mortality, particularly since World War II. Truly a wonderful thing, a major achievement, but the way we do it comes at a price in loss of habitat and biodiversity, among other problems that are discussed in other sections, such as equity, climate change and extreme weather events, air and water quality, plastic and chemical pollution and soil depletion/desertification.

These have profound effects on individual and population health, and we are set to lose many of those gains in a very fundamental and painful way. It has already started.

This far-ranging set of human technological disruptions in the global ecosystem has been termed the "Anthropocene." It was named as a new geologic era because the changes are so profound it will likely show up in the fossil record as a loss of biodiversity and an era of sudden extinctions. Not all agree with the name, but it has some power and traction.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity may sound “tree hugger” sentimental, but our living world depends on it, and so we humans do as well. When we lose “keystone species,” entire ecosystems degrade. A keystone species is one that if lost has profound effects on an ecosystem. The term keystone species was coined by the ecologist Robert Paine when he removed predatory starfish from tidal pools, and observed that the biodiversity of the pools decreased. The starfish ate mussels, and without the starfish the mussels took over and wiped out other species. We don’t always know what the tipping point will be.

We are losing species due to habitat loss (mostly for agriculture, but also for growing urban centers), pesticides and herbicides, industrial pollution, hunting/poaching and climate change.

We seem to be in the beginning of the sixth great mass extinction. Some estimate we are losing species at a rate 100-1000 times faster than “baseline.”

The other mass extinctions were much more prolonged geographic events, except maybe the meteor 65 million years ago that wiped out the dinosaurs; even that likely took time for all the dominoes to fall, and it wasn’t just dinosaurs. Vast numbers of species went extinct, making room for birds and mammals to flourish.

This is about potential ecosystem collapse. This is about the loss of plants, trees, kelp and plankton that supply the oxygen we breathe (plankton in the ocean supply about half of atmospheric oxygen) and sustain vast ecosystems we rely on. We also stand to lose many potential life-saving medications and sources of new foods.

How long can our human societies tolerate these disruptions? This is about sustainability writ large. It is about protecting our ability to survive and thrive.

The process can be reversed for some species and ecosystems. A famous example is the reintroduction of the gray wolf to Yellowstone National Park by the US Fish and Wildlife Service with Canadian biologists (the wolves were in Canada) beginning in 1995. Clearly biodiversity increased and the ecosystem was healthier after the wolves were reintroduced. The most well-accepted chain of events (though some debate whether it is the full story): the wolves ate the elk and deer that were too calmly eating young trees and other vegetation when they weren’t threatened by predators, which disrupted the ecology of the woodlands and riparian areas. When the wolves were reintroduced and the elk and deer numbers decreased due to wolf predation, or at least had to be wary and not have time to enjoy leisurely meals, plants and trees thrived, river banks were stabilized, and so beavers built dams, resulting in more types of watery habitats, and so more plants, and more species of many types that needed the water or the plants could be found in the park.

There are also concerns by those who live in the area outside the park, especially ranchers. Wolves don’t respect our boundaries, they follow the elk herds. When outside the national park they can and will be shot. This is a very difficult situation we see around the world with nature preserves. Whether dealing with wolves here or elephants in Africa, or in developing areas for ecotourism, the interests of the local human populations must be addressed as fairly as possible if these efforts are to be successful.

Sustainability is the ability to maintain production, in this case of an ecosystem, of the diversity of life. Resilience is the ability to bounce back and weather the storm. Both are needed and we are sorely taxing both.

The United Nations has published sustainability goals and the US Fish & Wildlife Service has information about endangered species.

Another aspect of biodiversity loss is invasive species. In some cases these were transported on purpose, in other cases inadvertently, by humans to new ecosystems. These species may not have evolved with the same natural conditions, including local predators, as in the ecosystem they now find themselves, and so can crowd out or outcompete local species, and take over or degrade the ecosystem by altering the balance of species and decreasing biodiversity.

There are many tales worth telling, but of particular relevance now vis-a-vis the effects of climate change are plants that create an environment that encourages the spread of wildfires. For example, invasive grasses grow quickly, get big, dry out, and become fuel. Many invasive plants and grasses were brought in to be ornamental. Quite a price to pay.

See also the section on “biosphere disruption” in the page “Why We Care.”

This great horned owl was displaced from its forest by a wildfire and spent a day lost and harassed by crows in a Los Angeles urban neighborhood, and moved on that night under the cover of darkness.

Monoculture

Monoculture refers to planting primarily one variety, or very few varieties, of a given crop. It is efficient and economical and usually works out, except when it doesn’t and millions may starve or the economy collapses.

If you plant only one variety of a crop, and there is a new pest or disease (or an old one evolves), and that one variety that was planted is now susceptible to that pest or disease, you are out of luck. Having many varieties gives you a shot that at least one will be resistant.

Unless you are a farmer who can plant diverse variations of food and rotate crops, there is little you can do directly, other than support those taking action and buy from those who plant diverse products and practice sustainable farming when that information is available. You can lobby your representatives and watch for relevant legislative or regulatory actions.

The European Union calls it “DiverFarming.”

There are large seed depositories that are amazing efforts, but they are not necessarily going to help a vast breakdown (say infection) of a major crop in a timely fashion to avoid much suffering and economic loss and disruption. But it is comforting to know they are there.

Pollinators

Pollinators include bees, butterflies and moths, and some birds and mammals, including bats. Many are having a rough time due to habitat loss, droughts, toxins and other human interventions.

Bees

Bee on pollinator plant in a yard in LA

We rely on bees to pollinate about a third of our food supply. If bees go, so does a great deal of our food.

Sure, there are other pollinators and foods that don’t require pollinators, but given the stresses on our food system due to a growing population and loss of soil and dwindling water for irrigation, the loss of a portion of a third of our food supply would likely be a dangerous tipping point. Prices rise, people go hungry, people die (mostly the poor and vulnerable), and social unrest and economic disruption ensue.

Bee collapse is best avoided.

We have known of bee colony collapse disorder for years. It seems to be multifactorial, from pesticides to mites to the usual suspects in our destruction and disruptions of life: habitat loss and how we use and treat the animals in our care. We must work to change this; many agencies, researchers, and environmental groups are on it.

Butterflies

Monarch caterpillar on native milkweed planted in a yard in Los Angeles

Butterflies are also pollinators.

We have lost a great deal of the population of monarch butterflies due in part to loss of milkweed that their caterpillars depend on. There has been an increase in monarch butterflies in California in the last year; we will see how long that lasts. Butterflies out west do not migrate to and from Mexico like those in the eastern US.

The El Segundo blue butterfly at the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve.

Many ecological groups are on this and can use your help. Of course, you can plant native or other plants that attract and nourish butterflies, just ask at your plant nursery. It is a joyous and rewarding thing to do.

You might find you have some time or can suggest volunteer opportunities to others. These can be through local chapters of large groups or local activities. For example, the Ballona Creek Marsh group in Los Angeles (Friends of Ballona Wetlands, www.Ballonafriends.org) and others planted sea cliff buckwheat (also called coastal dune buckwheat) to attract and nourish the El Segundo blue butterflies, which were on the brink of extinction and are now thriving. This is a great example of local groups making a difference.

Coastal wetlands are fast disappearing in the United States. More than half are gone, and that is more like 90% in California. Wetlands are a source of unique biodiversity which is different in different coasts around the world, from marshes to mangrove biomes.

These wetland ecosystems filter water, are a place for migrating birds to rest and eat, serve as a nursery for fish, and act as a buffer for floods and storm surges. More than 700 million people live on coasts around the world, including 40% of Americans, and their long-term economic security and infrastructure are hurt by our ongoing damage to these natural resources and flood barriers.

Toxins

Ever since Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring made waves six decades ago, we have been aware of the role of toxins like DDT in extinctions and ecological damage. Some feel that was a major kick start to the environmental movement.

Critics of strong environmental regulation say we overdid it by banning DDT and lost out on important tools for controlling insect vectors of disease as well as pests that eat our crops. We always need to consider a balance, of course. The problem is we don’t always know the full impacts of a pollutant.

The plan wasn’t for DDT to destroy animal populations; only insects were supposed to be targets. Animals ate the DDT poisoned insects and the poison accumulated up the food chain.

The California Condor, considered a keystone species, was decimated by brittle eggshells and infertility, primarily from DDT exposure. The Los Angeles Zoo, the San Diego Zoo, and others saved the California Condor. In 1982 only 22 birds remained. In 2017 there were 173 in captivity, 226 released into the wild from captivity, and 64 wild fledged.

As important as condors are to the ecosystem, if it were only one type of bird, maybe we could shrug our shoulders. But over time, would it just be the condor, would it just be birds? It was likely just the beginning, especially as DDT accumulated up the food chain and in our food system and so in us (even if we were not directly exposed, which we were in the 1950s, with great abandon). We don’t know exactly how bad this would have gotten, but it wouldn’t have been pretty.

Many chemicals we add to the environment are either insufficiently tested or without long-term surveillance. Many are not sufficiently tested to know if they are carcinogens or might cause other problems (sterility, birth defects).

Clinicians, of course, are involved when there are overt or acute toxic exposures, say of agricultural workers.

Even fertilizers that are not toxic per se can do damage to ecosystems we rely on for food. The commercial application of nitrogen fertilizers that wash off the fields, into streams, rivers and the sea or ocean can do great damage. In the American heartland much of the nitrogen washes from the Mississippi basin into the Gulf of Mexico, causing blooms of algae (some of which can produce neurotoxins) that use up the oxygen in the water, causing huge anoxic death zones.

To feed the huge global population perhaps we have no choice but to make some compromises. Organic farming may not be able to scale up (though I encourage those who can afford it to buy organic products). But we must be as judicious as possible, and decisions must not only be determined by more profit.

The NIH has a 2016 technical summary of the nature of available pesticides.

This is a short outline summary of health effects of pesticide exposure out of Canada, just to give a taste. These are poisons that in a high enough dose poison humans as well!

Industrial pollution

Air pollution is dealt with separately.

The subject of industrial and nuclear waste pollution is vast. We can vote for those who will help provide oversight, and try to clean up and regulate this mess. The money from vested interests that goes into lobbying is difficult to fight in the American political system where the idea that “money talks” has been codified by the Supreme Court.

Extinction

Extinction is forever. Sure, you will read stories of species thought to be lost that then show up, but that is rare. Don’t be lulled into thinking it isn’t a big deal. We don’t know what could be the tipping point, the start of a critical and irreversible downward spiral. Previous great extinctions wiped out as much as 90% of life on Earth, and they sometimes took many millennia to do it, so we are moving much faster toward a mass extinction; we won’t take millennia!

See The Sixth Extinction, an unnatural history. Elizabeth Kolbert. Picador Henry Hall and Company, 2015. A well written best-seller if you are interested in the big picture.

“1 million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades”: UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates "Accelerating” From the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Lost species not only might crash ecosystems and decimate our food supply (think pollinators), but they are also lost opportunities. Species that go extinct before we know much, if anything, about them might have had properties that could have been medically useful. As healthcare professionals this cuts close to home, as it does for many patients. Think of the increases in antibiotic resistance, in part due to our unsustainable agricultural practices where antibiotics are used to grow meat faster. We need sources of new antibiotics, and these have often come from microbes and plants. It would be terrible, as well, to lose tamoxifen, a useful anti-cancer agent, or to have never discovered it in the first place, if the yew tree was lost. How many others are we losing every day?

Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Atanasov AG et al Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 20,200-216 (2021)

Additional Resource

The Convention on Biological Diversity is part of the “United Nations environment programme.” This website has a lot of news on the homepage alone, and the topics section is a rich source of information.